Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

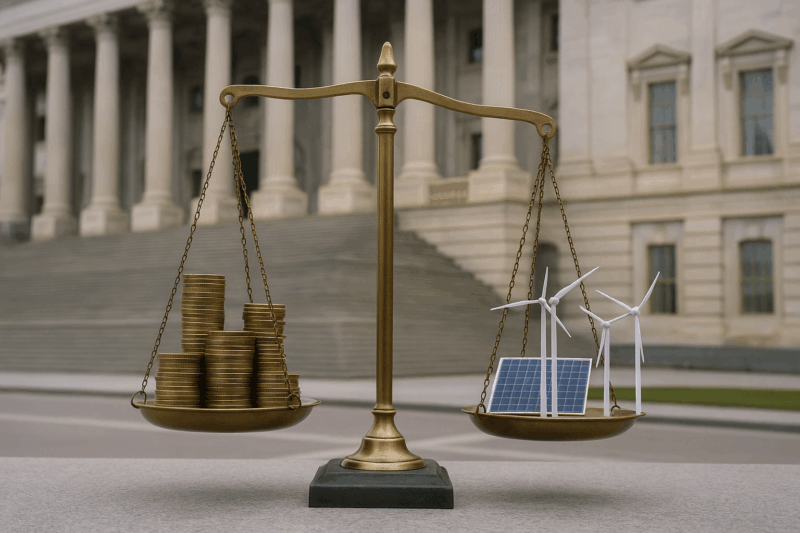

Brett Christophers has put his finger on an uncomfortable truth. Renewable energy has reached the point where it is often cheaper to generate than fossil fuels, yet the rate of investment is still far below what climate targets demand. His book, The Price is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet, explains why.

Investors follow profit, not need, and renewables are structured in a way that turns falling costs into falling revenues. Solar panels and wind turbines produce power at near zero marginal cost, so competition drives prices down. That is good for consumers and good for emissions, but it makes for wafer-thin profit margins that are not attractive to capital looking for steady, high returns. Fossil fuels by contrast remain in many cases more profitable because their scarcity can be controlled and their markets are designed to reward incumbents. Christophers’ conclusion is stark. If profitability is the bottleneck, then leaving the transition to private capital will not work at the speed required. The state must take on a far larger role.

The core of his argument is hard to dispute. If companies and financiers do not see an acceptable return, they will not deploy capital. He documents how even record low bids for renewable projects have been followed by cancellations or pleas for more support when inflation or supply chain pressures squeeze margins. He reminds readers that what has been built so far has leaned heavily on subsidies, tax credits, or guaranteed contracts, not on free market enthusiasm. Without that scaffolding, private developers walk away. It is a useful correction to the triumphalist narrative that renewables will sweep the board simply because they are cheaper on paper.

Christophers’ prescription for action is that governments must move beyond reliance on markets and take a leading role by building and owning renewable infrastructure themselves, or through public utilities and agencies. Where private developers are involved, he insists that the state must guarantee returns through long-term contracts, subsidies, or price supports that stabilize revenues.

He frames electricity as a public good ill-suited to volatile spot markets and better managed through planned, coordinated investment in generation, grids, and storage. In short, he calls for a decisive expansion of state leadership and ownership, with private capital relegated to a supporting role under strict public frameworks, on the grounds that only by bending or bypassing the logic of profit can the transition proceed at the pace the climate crisis demands. Basically, he calls for socializing electrical generation and removing markets from the equation.

However, credible critics have pointed out that the story is not quite that simple. Renewable profitability varies by technology, geography, and market design. A rooftop solar installation in Germany is a different investment proposition than offshore wind in the North Sea or utility-scale solar in Texas. Many economists note that market design can be reshaped to stabilize revenues. Contracts for difference, long-term power purchase agreements, and capacity payments already exist in many jurisdictions and have drawn in billions of dollars of private capital. Others stress that non-financial bottlenecks such as lengthy permitting, overloaded interconnection queues, and grid congestion slow the pace of deployment even when investment appetite is strong. Christophers is right to highlight profit as a barrier, but it is not the only brake on progress.

There are also fair cautions about his solution. Public ownership can deliver long-term capacity, but state-run utilities have mixed track records, and governments face their own constraints, from budget limits to political interference.

The real question is not whether capitalism must be abandoned but how far it must be bent to public purpose. History offers a guide. Almost every major infrastructure build in the past century combined public rule-setting with private execution. Railroads, highways, telecommunications networks, and electricity grids were all made possible by government interventions that made them investable. The clean energy transition will be no different. The challenge is to design frameworks that unlock capital while ensuring deployment at the necessary pace.

One tool is market design that ensures adequate returns. Electricity markets that rely on energy-only spot prices expose renewable projects to extreme volatility. When the sun is shining or the wind is blowing, prices collapse, sometimes to zero or even negative, and investors cannot rely on a steady cash flow. That makes banks reluctant to lend without charging a high premium. Instruments like contracts for difference in the UK solve this by guaranteeing a fixed price for generation over 15 to 20 years. Developers bid competitively, which keeps costs down for consumers, but they know exactly what revenue they will earn, which makes projects financeable.

Long-term corporate power purchase agreements play a similar role, although Christophers notes that large buyers often negotiate very low rates that squeeze developers. Capacity markets and ancillary service payments can also provide steady income for being available to the grid, not just for producing power in a given hour. These tools stabilize cash flows and lower the cost of capital, which is critical for capital intensive technologies like wind and solar.

Another tool is public support for finance. Governments can use green banks, loan guarantees, or co-investment funds to take on part of the risk that deters private lenders. A green bank providing low interest loans, or a public entity taking the first loss in a project portfolio, can make the difference between a renewable project being bankable or shelved. The Inflation Reduction Act in the United States was an example of public money creating private profitability. Generous tax credits and direct payments made clean energy projects attractive to investors, and as a result the pipeline of solar, wind, and battery plants expanded dramatically. This is capitalism with a thumb on the scale, and it shows that policy can shift capital quickly when it aligns profits with climate goals.

There is also a role for direct public investment in infrastructure the market will not build on time. Transmission lines, interconnectors, and large-scale storage are expensive, slow to permit, and often unprofitable for private firms to build on their own. Yet without them, renewable projects remain stranded. Governments can and should take the lead on these backbone elements, whether by funding them outright or by creating regulated monopoly frameworks that guarantee returns. The payoff is that private developers can then connect new projects without prohibitive delays. Public ownership is justified in these cases because the social value of expanded grids and storage far exceeds the private return.

Carbon pricing and clean energy standards are additional levers. By making fossil fuels more expensive or mandating a rising share of renewables in electricity supply, governments tilt the economics decisively. A robust carbon price or an enforceable renewable portfolio standard creates predictable demand for clean power. That demand, in turn, gives investors confidence that their projects will have a market. These policies are not without political difficulty, but they are well within the toolkit of capitalist economies.

Reducing soft costs is another area where policy can raise effective returns without raising consumer bills. Every month cut from permitting timelines or interconnection delays improves the net present value of a project. Standardized contracts, transparent grid data, and faster regulatory processes all contribute to making renewables more attractive investments. This is not about subsidies or public ownership, but about making the system function more efficiently.

There are selective cases where public ownership makes sense. Grid infrastructure is one. Repowering old coal sites with renewables where transmission already exists is another. Early stage offshore wind zones or large storage projects may also benefit from public build-own-operate models, especially if private capital is hesitant. The key is to ensure such ventures are governed transparently, with clear mandates to deliver reliable, low-cost clean power, not to serve as political tools.

Evidence from around the world supports this blended approach. The UK’s offshore wind boom was driven by contracts for difference that de-risked investment. The United States is seeing a surge of projects thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits and loans. China’s massive buildout of wind and solar is guided by state planning and executed by both state-owned and private firms. Each case shows that when government sets the ground rules and shoulders part of the risk, private capital will scale clean energy. The common thread is that markets are not left on their own. They are bent to serve a public purpose.

As a note, this is one of a select group of books I’ve read which does an excellent job of assessing a complex space and clearly identifying issues, then veers off course into fairly bad prescriptions for action. Marx’ Communist Manifesto did an excellent job of identifying issues with capitalism, then offered a terrible alternative. Naomi Klein’s No Logo‘s first half was a master class in branding, and I learned a lot from it, but the second half was a laundry list of mostly meaningless resistance, not a useful alternative. The Price Is Wrong falls into this category, and for anyone seeing a trend here, you aren’t wrong. All three are worth reading for the diagnosis of the problems, but the strategic policies and plans are shaped by bias, aren’t relevant, and are clearly better resolved within the framework of market economies than through removing markets from the equation.

The conclusion is straightforward. Addressing Christophers’ challenges does not require abandoning capitalism. It requires writing rules that make clean, reliable power profitable to build and cheap to buy. Capitalism will not save the planet on autopilot, but it can be harnessed if governments are willing to set the terms. The measure of success is not ideology but delivered clean terawatt-hours at stable prices. The faster policymakers align markets with that outcome, the faster the transition will proceed.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy