Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

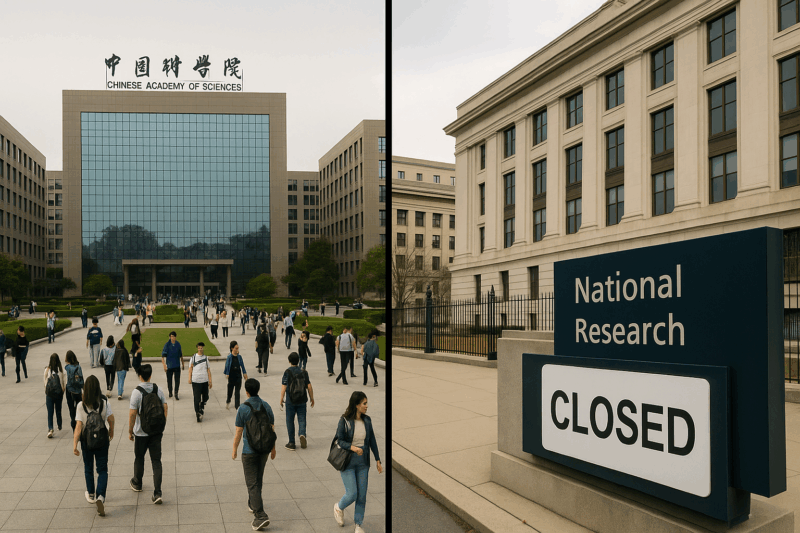

According to the latest Nature Index results, Harvard University is now the only American institution left in the top ten list of research organizations by contributions to leading scientific journals. It sits in second place, but far behind the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), which has pulled ahead by a wide margin.

The index tracks research output in selected natural and health science journals and uses a metric called Share. A paper counts as a single unit of credit that is split fractionally among institutions based on the authorship. Over the course of a year, the totals provide a measure of how much a university or research organization has contributed to the journals the index tracks. It is not the whole picture of global science, but it is a useful lens for comparing relative leadership.

The most striking element in the 2025 list is how thoroughly Chinese institutions now dominate. The Chinese Academy of Sciences posted a Share of 2,776 for 2024, while Harvard managed much less than half of that at 1,155. Eight of the top ten institutions are Chinese. Out of the top fifty, twenty six are Chinese, and collectively they hold close to 60% of the total Share. Names that were once minor in global discussions of science, such as Zhejiang, Nanjing, or Sun Yat-sen University, now appear alongside Peking, Tsinghua, and the University of Science and Technology of China. The country has scaled up STEM education, built vast research infrastructure, and expanded PhD output for two decades. The result is not just more papers, but a network effect where more researchers and laboratories reinforce one another, raising both quantity and quality.

The United States still shows up in the numbers, but the picture has shifted. Stanford, MIT, UC Berkeley, and UC San Diego all remain in the top fifty, but only Harvard has managed to hold on to a spot in the top ten. In relative terms, the gap is widening. The reasons are not mysterious. Public universities have been underfunded compared to their peers abroad. Federal research spending has grown slowly, and in some cases has been cut outright. Immigration restrictions have made it harder for foreign students and postdocs to contribute, despite the long history of the US benefiting from global talent. The political environment has become openly hostile to higher education in recent years. The Trump 2025 administration has cut federal research budgets, attacked universities, and targeted science agencies with funding reductions and leadership purges. That does not create a climate of confidence for either domestic researchers or international scholars deciding where to build their careers.

Europe has managed to remain steady, though not at the top. Germany’s Max Planck Society and Helmholtz Association, France’s CNRS, and Britain’s Oxford, Cambridge, Manchester, and Edinburgh are still in the top fifty. Europe’s institutions are not growing in Share as quickly as China’s, but they are not collapsing either. They benefit from a mix of long traditions in science, public funding, and stable research ecosystems. Their challenge is fragmentation. Unlike China’s centralized push or the US’s historic national research programs, European science is spread across multiple countries with varying policies. That reduces the ability to move quickly at scale.

The broader Asia-Pacific region beyond China also features prominently. Japan’s University of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Nagoya, South Korea’s Seoul National University, and Australia’s Melbourne and Queensland remain globally relevant. Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University is also in the mix. These institutions contribute important research, but in aggregate they make up a smaller share of the total. As a note, while Nature listed Hong Kong’s institutions separately from China, I counted them with China.

Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah University of Science and Technology appears at number fifty, a reflection of targeted investment in research as part of economic diversification plans. Also in the list is my alma mater, the University of Toronto, which I was pleased to see.

The strategic implications of this shift are significant. Where the leading science is done affects where technological breakthroughs originate, which in turn shapes global economic and geopolitical influence. In the twentieth century, the United States dominated in both scientific output and technological innovation. That leadership is now contested. China’s dominance in the Nature Index is not just a set of numbers. It reflects where discoveries are being made and where global talent may decide to concentrate in the future. For the US, a retreat from funding and supporting universities and research agencies risks hollowing out its innovation ecosystem. For Europe, failing to act in concert risks ceding more ground to both China and the US.

In my recent writing on the Trump administration’s treatment of research and universities, I have drawn comparisons to moments in history when governments turned against their own knowledge institutions. I argued that the budget cuts, ideological purges, and public hostility toward higher education echo Mao’s Cultural Revolution in their intent to suppress expertise and enforce conformity. The deliberate dismantling of programs at NASA, NOAA, and the EPA recalls the bonfires of books and scientists driven from their posts under authoritarian regimes. What we are witnessing is not an accident of budget priorities but an attack on the very infrastructure that underpins innovation and prosperity. By targeting universities and federal research agencies, the United States is following a path that has been tried before, always with the same result: diminished capacity to create, to compete, and to lead.

The Nature Index is not a perfect measure. It covers a curated set of journals and focuses only on natural and health sciences. It does not include engineering, applied research, or social sciences. But the trends it shows are too clear to ignore. China is investing in fundamental science at a scale unmatched by any other country today. The United States is still producing leading research but is losing relative ground. Europe is stable but fragmented. The rest of the Asia-Pacific is holding on with smaller shares. Countries that invest in science are reaping both academic and industrial returns, while those that retreat are risking long-term competitiveness.

Harvard remaining in second place provides a symbol of what was once a broad American dominance. Now it stands as an outlier among a list crowded by Chinese institutions. The future of global research leadership will depend on policy choices in the next decade. If China continues to expand its commitment to research and education while the United States and others continue to cut, the realignment could become permanent. The world is watching where discoveries are made and where the next generation of scientists will train. These numbers suggest that the balance has already shifted and may keep shifting further.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy