Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

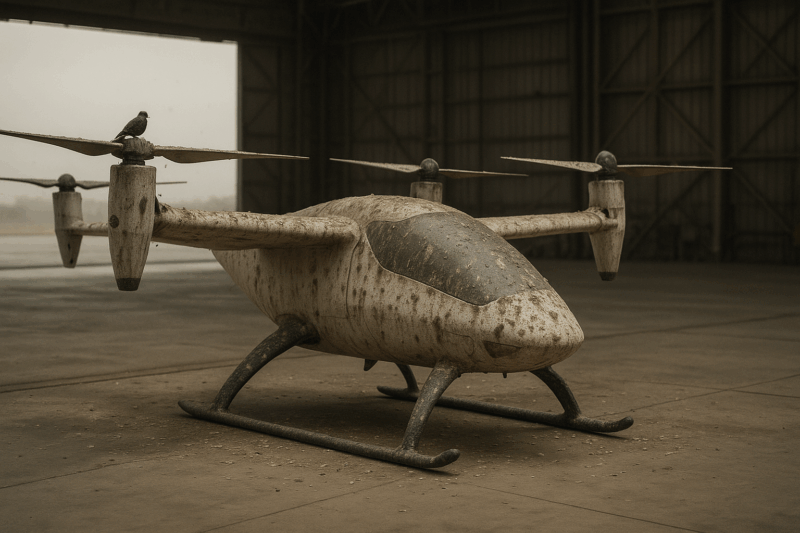

Supernal’s decision to pause work on its eVTOL aircraft is a signal that the sector is entering a different phase. Hyundai created Supernal with strong funding, a long timeline, and a clear plan to bring a five-seat air taxi to market around 2028. If a global automaker with significant resources is stepping back, it shows the headwinds facing the entire industry. Supernal’s leadership departures and restructuring underline the difficulty of moving from prototypes to certified aircraft and then to viable operations.

The broader landscape of eVTOL development looks very different from the early hype. Out of 32 companies I’m tracking, 7 have already abandoned their programs, 3 are operating in limited commercial niches, 1 has pivoted into another line of business, and 21 remain in pre-production. Most of these firms raised money during the peak of investor enthusiasm, with public valuations and hundreds of announced pre-orders. The picture in 2025 is much more grounded. Only a handful of companies are flying real routes with paying customers and those operations are limited in scope and geography.

For years, we’ve been sold on two futuristic transportation dreams — hydrogen vehicles and eVTOL air taxis — as clean alternatives, but the fantasy is finally running headlong into economics, physics, and regulation. Hydrogen simply can’t compete: battery technologies are getting cheaper, denser, and more reliable; hydrogen production and transport remain costly and leaky, and the fuelling infrastructure and vehicle reliability don’t hold up in real‐world conditions.

Meanwhile, eVTOL developers have overstated their markets, under-estimated costs (especially for certification and safety), and ignored the operational challenges of flying over cities under real weather and regulatory constraints. As I track the “deathwatch” of firms in both spaces — not just startups but established players with hydrogen or eVTOL initiatives — it becomes clear. All are losing money, some are folding, and many more are at risk. In short, the hype is unravelling, and what was presented as inevitable is looking increasingly avoidable.

The abandoned group includes some high-profile names. Kitty Hawk shut down in 2022, taking its Heaviside project with it. Lilium declared bankruptcy again in 2025 after promised funding fell through. Volocopter entered formal insolvency proceedings in Germany in late 2024. Rolls-Royce exited its electric propulsion line. Airbus paused the CityAirbus program. Each case points to the same problem. Building a safe, reliable, affordable eVTOL that passes certification and enters service is far harder and more expensive than early forecasts suggested.

The operational companies are not running urban air taxi networks. EHang is flying short sightseeing loops in China with its EH216-S, approved for commercial passenger use on fixed routes. AutoFlight is delivering certified one-ton cargo autonomous aircraft in China. Jetson is shipping its single seat ultralight personal vehicle to wealthy enthusiasts. None of these match the vision of large networks of eVTOL taxis carrying thousands of passengers a day across congested cities. They are interesting, but they are not the revolution that investors were promised.

The firms still in pre-production include Archer, Joby, Vertical Aerospace, TCab Tech, SkyDrive, and others. They are building and flying prototypes, raising new funding rounds, and publishing timelines for certification in the second half of the decade. Archer and Joby in particular have made progress with the FAA and continue to attract capital. Yet even they face years of testing, safety validation, and infrastructure development before commercial entry. Most of the rest will struggle to survive the long gap between demonstration flights and certification.

The challenges are consistent. The economics of urban air taxis are difficult. An aircraft costing millions must fly many hours per day at high load factors to cover capital and operating costs. Battery energy density limits range and payload. Downwash, noise, and turbulence make rooftop or street-level operations problematic. Wind and weather limits reduce availability. Certification requires thousands of flight hours and proven safety redundancies. Air traffic management for autonomous or semi autonomous craft is not ready. Public acceptance of low-flying rotorcraft over dense cities remains uncertain.

Supernal’s retreat matters because it shows that deep pockets do not solve these issues. Hyundai had the money, engineering talent, and manufacturing experience to give its program a real chance. If it cannot see a path to profitable operations, that suggests the air taxi model itself is flawed. Airbus reached the same conclusion earlier in the year when it paused its program. Rolls-Royce made the same decision with its propulsion unit. Volocopter’s insolvency is a direct result of running out of time and money before certification and revenue could arrive.

The survivors are adapting. Cargo is often the first application, as with AutoFlight or Pipistrel’s Nuuva. Tourism and sightseeing offer another near term market, as with EHang. Personal recreational aircraft like Jetson, Skyfly, and Pivotal may find buyers in the same way small planes and high end sports cars do. But none of these are the mass transport solution that eVTOL promoters described five years ago.

This pattern is familiar. Hydrogen was touted as a fuel for cars, trucks, and aircraft. Billions were invested. A few niche applications remain, but battery electric has won most markets. The similarities with eVTOLs are striking. Both were promoted as transformational. Both had enthusiastic investors and governments. Both faced physics, economics, and infrastructure barriers that were not overcome. The hype period was followed by a long series of contractions and consolidations.

Looking out to 2030, most of the 21 pre production eVTOL firms will not reach certification or sustained commercial service. A handful may survive by focusing on niches where economics are better, regulation is lighter, or customers are willing to pay for novelty. The idea of dense networks of air taxis replacing ground transport in major cities isn’t going to arrive in this decade, and likely not at all. The more credible transformation of aviation will come from electric regional aircraft with fixed wings. They can use existing airports, carry more passengers, and take advantage of the rapid improvement in batteries and electric propulsion.

Supernal’s folding is symbolic. The era of hype is ending. The sector is moving into an attrition phase where many firms will fail, a few will survive, and the market will settle into niches. The original promise of eVTOLs as a mass urban transport solution is receding. The story now is about how a vision of the future met the hard reality of physics, economics, and regulation, and how an industry will be reshaped in the aftermath.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy