Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Can a small island community—through art, innovation, and co-design—demonstrate what’s possible for sustainable infrastructure across the Pacific and beyond?

Coastal island communities are especially vulnerable to climate change. Stronger cyclones, rising sea levels, warming waters, biodiversity loss, prolonged droughts, and major flood events threaten their existence. Marou Village in the Yasawa archipelago of Fiji is one such community.

The residents of Marou Village and Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI) partnered to co-create a unique design competition that would redefine what infrastructure can be. Together they invited anyone interested to design a work of art in the landscape that will supply clean and reliable electricity and drinking water to the coastal village’s 67 households, support tourism, and help to build a sustainable future for generations to come.

While electricity is a pressing need in Marou Village, also of critical importance is ensuring reliable access to freshwater. As global temperatures rise there is increasing variability and volatility in precipitation patterns. Rainy seasons bring severe flooding while dry seasons are even drier. LAGI 2025 Fiji, therefore, sought innovative solutions that can integrate regenerative energy and water systems. Energy is the primary system for which LAGI 2025 Fiji was seeking design solutions. In order to qualify, an entry must have provided a 75 kW or greater solar photovoltaic mini-grid for the Village of Marou within the energy design site.

The competition had their work cut out for them – they had to respond to the context and challenges of this remote South Pacific village. From 205 submissions representing 45 countries, two proposals were chosen by a local and international jury for their ability to listen to the land, climate, and community.

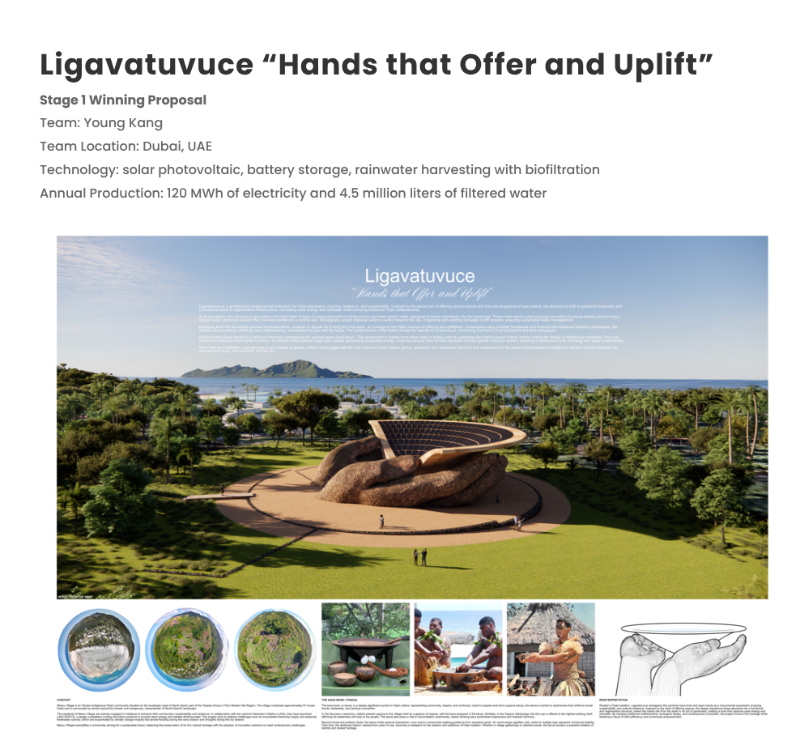

The winners of the LAGI 2025 Fiji design competition are now public. The two winning visionary artworks-in-the-landscape are designed to generate clean energy and water while reflecting the hopes of Marou residents for a future grounded in environmental stewardship and cultural identity. Each team has been provided with $100,000 to advance their design proposal and build a functioning prototype of their idea in Fiji.

These installations will meet the village’s electricity and clean water needs while serving as vibrant public spaces rooted in cultural tradition. The prototypes will be exhibited in Suva in early 2026, after which one project will be selected for full-scale construction in Marou in coordination with local authorities and funding partners. The outcomes will set a replicable model for designing, implementing, and operating renewable energy and water systems with island communities and for exquisite destinations around the world.

A book published by Hirmer Verlag will include 83 submissions. Exhibitions of dozens of submissions will be held in partnership with the Fiji Arts Council opening on November 6, 2025. The submissions support Fiji’s stated policy of deriving 100% of national electricity production from renewable energy sources by 2030 and achieving net-zero annual greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

The Back Story to the Fiji Village’s Climate Infrastructure Problems

The real story here is not only about what is being built — it is how. From the start, LAGI 2025 Fiji was co-designed with the people of Marou. Villagers gathered in workshops and ceremonies to shape the design brief line-by-line. They defined the needs, constraints, and aspirations of the project, informed by lived experience: worsening floods in the wet season, severe droughts in the dry, and unreliable access to energy and potable water. They spoke of their desire to host visitors and to ensure that any new infrastructure would be operable for generations to come.

Too often, rural communities receive prepackaged systems—rows of ground-mounted solar panels, diesel replacements, or modular water units—that are dropped in with no plan for training or upkeep. When these systems fail, as they frequently do, the problem isn’t just technical—it’s social and structural. Without knowledge transfer, without community investment in the outcome, infrastructure becomes alien. It falls into disrepair, and with it goes trust.

LAGI’s approach challenges that cycle. Rather than enclosing technology behind fences, the projects in Marou aim to make infrastructure participatory—to turn solar and water systems into spaces of cultural gathering, celebration, and resilience. By rooting the process in Fijian values and material traditions, the installations are more likely to be maintained and cherished long after the designers depart.

The implications go far beyond Marou. As Fiji confronts sea level rise and increasingly extreme weather, and as the country aims for 100% renewable electricity by 2030, the lessons of this village-scale intervention could ripple outward. The model being tested here—of co-creation, aesthetics, and circular resource use—offers an alternative to centralized, carbon-intensive development.

“There’s a difference between installing technology and building a relationship,” said Elizabeth Monoian, LAGI co-founder. “When communities help design their own systems, they’re more resilient—not just technically, but socially.”

Marou Village, Fiji: A Study in Resilience

Marou Village is an iTaukei community on the southeast coast of Naviti Island in the Yasawa Group archipelago in the Western Ba Region of Fiji.

Two of the village’s greatest pressing needs are reliable electricity and year-round access to freshwater. Better access to electricity in Marou will help run water pumps, provide better lighting, refrigeration, energy storage, digital banking, telecommunications, device charging, and power the tools and equipment that will allow small local businesses to thrive.

Marou regularly floods during the multi-day rain events that are common during the rainy season. Water channels have been eroding the land in and around homes. And yet for half of the year during the dry season, freshwater can become dangerously scarce. Meanwhile, rising seas threaten to contaminate underground wells with saltwater. For these reasons, innovations for rainwater harvesting, filtration, and storage were a central component of the LAGI 2025 Fiji Design Guidelines.

Other community needs include spaces for shade, agriculture/aquaculture, recreation, education, and shelter from severe storm events.

Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI)

The Land Art Generator Initiative has been working in communities around the world since 2010 to leverage the power of art and design to accelerate the global response to climate change. LAGI design competitions are opportunities to re-think conventional ideas and put forward exceptional solutions for sustainable systems designed to double as beautiful places for people — regenerative works of art for landscapes, cultural sites, destinations, and public parks — creating shared land uses and co-benefits for healthy communities.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy