Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

I recently read Why Nations Fail, the 2012 book by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, who won the Nobel Prize in 2024 for Economics for their work on how institutions shape economic prosperity, and was struck by how confidently it placed the United States on a path of enduring greatness. The authors highlighted America’s pluralism, its rule of law, and its willingness to allow creative destruction as features that would sustain prosperity.

By contrast, China, in their telling, had engineered a temporary boom under extractive political institutions but would stall before reaching true prosperity. Critics at the time pointed out that the book had very little empirical data on China, limited anecdotal data and a clear tendency to assert that the pattern the USSR took was inevitable for China. To me it had a clear odor of Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” smugness.

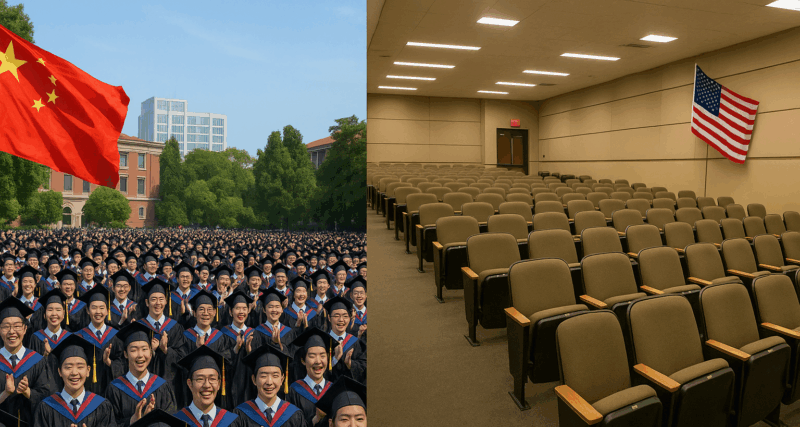

Sitting in 2025, it is hard not to notice how this forecast feels inverted. America is attacking its own institutions while China is surging in education and technology deployment. The frameworks in the book remain powerful, if too binary to reflect real-world complexities in my opinion, but the trajectories they anticipated have diverged.

The central argument of the book is that inclusive political and economic institutions underpin lasting prosperity. When broad groups of people have access to power and opportunity, when property rights are secure, and when innovation can flourish, societies grow stronger. When power is concentrated in the hands of a narrow elite, when the rule of law bends to political expedience, and when incumbents fear creative destruction, the result is stagnation. This lens provides a useful way to look at both America’s recent political climate and China’s institutional choices.

In 1990, the United States was a textbook case of a virtuous institutional circle. Courts, Congress, and the presidency respected each other’s roles. Scientific research enjoyed stable support. Immigration brought waves of talented students and entrepreneurs. Creative destruction was not feared but celebrated, as industries rose and fell in a dynamic economy. That institutional baseline stood in sharp contrast to the brittle systems of many other nations. In 2025, the picture is more complicated. The United States under Trump 2.0 has seen open challenges to constitutional limits, purges of professional civil servants, and attacks on universities and research bodies. Each breach of norms makes the next easier, creating a vicious circle rather than a virtuous one.

Creative destruction is at the core of this reversal. America historically allowed new entrants to disrupt industries. Antitrust enforcement, venture capital, and the culture of Silicon Valley embodied this principle. Today the country is increasingly afraid of creative destruction. Sweeping tariffs have been erected to protect legacy industries. Energy policy is tilted toward preserving coal and oil. Research universities and federal science agencies are under political attack, undermining the pipeline of ideas that fuels innovation. Immigrants are demonized instead of welcomed. When the Trump Administration attacks universities as enemies and defunds basic science, it is dismantling the very foundation of future prosperity.

China provides a stark contrast. In 2012, the authors’ expectation was that its extractive politics would choke innovation. Yet China has doubled down on education and produced a massive advantage in STEM graduates. Every year, millions of engineers, scientists, and technicians emerge from its universities and vocational programs, not to mention the flood of Chinese foreign students in the best universities globally. By sheer scale, China produces far more technical talent than the United States, and it has maintained steady support for research. It is investing heavily in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and advanced materials. While American politicians disparage higher education, Chinese leaders continue to treat it as a national asset.

China’s handling of its internet commerce giants compared to America’s treatment of Google illustrates another divergence in institutional choices. In recent years, Beijing moved aggressively to curb the power of companies like Alibaba and Tencent, breaking up monopolistic practices, tightening financial controls, and forcing structural changes to prevent any one platform from dominating the economy. The intent was clear: keep space open for new entrants and avoid entrenched incumbents dictating terms to the market.

In the United States, by contrast, regulators have allowed Google to maintain its overwhelming dominance in search and digital advertising with only limited antitrust pressure. Rather than safeguarding creative destruction, American institutions have tolerated concentration, leaving a handful of firms with immense influence over information flows. From the perspective of Why Nations Fail, China’s intervention looks more like a state attempt to preserve dynamism, while the United States is drifting toward protecting incumbents at the expense of broader innovation.

The pattern is even clearer in clean technology. China has absolute leads across solar manufacturing, wind turbine supply chains, batteries, electric vehicles, heat pumps, and high-voltage grid electronics. It has built the factories, trained the workers, and financed the scale-up. Learning curves in these industries mean that costs fall with each doubling of capacity, and China is accelerating those doublings.

The United States, on the other hand, is erecting tariff walls against Chinese clean technologies and slowing its own deployment. Protecting legacy energy sectors while raising costs for renewables does not align with creative destruction. It entrenches incumbents and delays the transition to the industries of the future.

The book’s framework of de jure versus de facto power is also relevant. In a healthy system, legal power and actual power align. In 2025, the United States has seen growing gaps. Courts block executive actions only to face threats of being ignored. Pardons have been issued to political allies involved in attacks on democratic processes, notably all of the Jan 6 insurrectionists. Civil servants have been stripped of protections and replaced with loyalists. These moves concentrate de facto power in ways that exceed what the law envisions. For innovators and investors, this creates risk and uncertainty. If policy can shift overnight based on personal loyalty rather than rules, long-term bets on new industries become far less attractive.

The ICE raid at the electric vehicle battery plant in Georgia adds another layer to the institutional pressures undermining America catching up in clean technology. In early September 2025, federal agents detained nearly 475 workers at the Hyundai–LG plant under construction — about 300 of whom were South Korean nationals — on immigration visa charges. This enforcement action led South Korea to send a chartered plane to repatriate detained workers while seeking assurances that they could return lawfully, even as construction paused and foreign firms reconsidered future investment in the U.S.

Critics warned that such unpredictable enforcement chills the inflow of skilled foreign labor needed to build advanced factories. In the context of the broader argument, the raid illustrates how fear-driven policy hampers creative destruction and disrupts the institutional foundations, including global talent flows, that once powered American industrial innovation.

Pluralism has also eroded. In 1990 both parties accepted the legitimacy of their opponents and institutions. Today political discourse often paints opponents as enemies of the people. Media and academia are labeled as adversaries rather than pillars of pluralist debate. Trump praises international strongmen who centralize authority and repress dissent, signaling admiration for absolutism rather than pluralism. That undermines the expectation that multiple voices will shape policy and weakens the checks that encourage broad-based prosperity.

Policy choices tell the same story. Tax and regulatory moves this year are heavily tilted toward the wealthy and toward favored industries. The idea of broad-based policymaking, which characterized many decisions of the late twentieth century, has given way to elite-concentrated decisions. Tax cuts and deregulation are designed with the interests of a narrow group in mind. By contrast, inclusive policymaking would prioritize public goods like education, healthcare, and clean infrastructure that benefit the many.

The result is a widening gap between the two institutional trajectories. China still operates under an authoritarian party structure, but it has created effective state capacity, strong meritocratic promotion in its bureaucracy, and massive investment in education and clean technology. The United States still has democratic institutions, but its recent choices show elements of absolutism, extraction, fear of creative destruction, and elite capture. The irony is that the country held up as the model of inclusiveness in 2012 is testing the boundaries of absolutism in 2025, while the country dismissed as extractive has captured the commanding heights of the next industrial era.

The lesson from Why Nations Fail is that prosperity is not guaranteed. Institutions matter, and they can degrade if not protected. America’s future depends on restoring support for research, reopening to talent from abroad, recommitting to the rule of law, and embracing the disruptive industries that will define this century. Creative destruction is not comfortable, but it is the engine of progress. Nations that fear it stagnate. Nations that welcome it thrive. In 2012 the United States embodied that confidence, and clearly China understood it for businesses and markets, if less so for political power. In 2025 the Trump Administration is clearly aiming for an extractive, absolutist rule that benefits only the elite, with long term negative outcomes for the country, and is succeeding.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy